Introduction

It was impulse that led Kati Garner to fame and recognition as the

first woman to go through and graduate from the United States Navy Diving School. In this traditional male-only world, even some of the strongest men

can't make it. That's how tough it is. But Kati did, and her feat cannot be attributed to muscles or physique, because this blue-eyed girl is only 5'3"

tall and weighs 115 pounds "Punk," as they called her, ran five miles, did 500 flutter kicks, and swam a minimum of one mile anytime she was directed

to, along with the toughest and roughest of her fellow students.

|

|

Kati, who was born in Colorado Springs on May 9, 1953, is an unusual girl from a usual background. The whole Navy scheme came into being when Kati was

in her second year at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois.

"I was getting dissatisfied with school and living at home and wanted to get out and do things," she said. Kati joined the Waves and, at age 19, was off

to Orlando, Florida, for boot camp. At that time, diving was something she had never done and the idea of it didn't even occur to her. She was going to Personnel School, "to learn how to sit behind a desk and typewrite all day."

Kati became dissatisfied again, but dragged herself through the program, wondering what in the world she was doing. One day one of the teachers asked

if anyone wanted to go into the UDT Seal Team, to go into diving. Tiny Kati raised her hand. "They all looked at me and laughed," Kati said, "but I like

to do things on the spur of the moment, kind of impulsive, you know?" |

Dive school

Nine months went by before Kati was finally transferred to the Personnel Office in San Diego to perform similar

disinteresting tasks in a similarly disinteresting office. Then one day someone announced that the Commander was

looking for women for the dive school. Kati put her request slip in and began to wait, again. Three other women in the office also put their names

in the hat. Kati was ready to start conditioning herself and suggested that they all get in shape. The others said they would wait until later and, with

that, Kati decided to go on her own, even though she didn't know if she would he accepted in the school or not.

Along came SCM (DV) Robert D. Diecks, Swim Coordinator at the Recruit Training Center, who appointed himself as Kati's coach, to prepare her for

the tortuous ordeal she faced. "She needed stamina," said Diecks. "When she started she couldn't even run a quarter mile." So, every morning at 0600,

Kati and Bob would be out on the track. By the end of three months, Kati was running three miles with ease and doing 40 regulation pushups in one

session. Every day they would do calisthenics, sit-ups, flutter kicks, and then top it off with swimming marathons. Kati recalls, "I'd say, 'Stop!

Stop!' and Diecks would say, 'Keep going!"' Diecks explained to Kati that the U.S. Navy would made no exceptions because she was a woman.

The preparations went from September to November. Kati entered the diving school on November 5, 1973. One other woman was accepted for the four-week

course. |

|

The first Tuesday of the diving school training is known traditionally in the school as "Black Tuesday," and for good reason: "They give you a pretty

rough hour of calisthenics. They got us out there and made us run after every exercise, they wore us out, and then they had us play leapfrog with

about 23 guys. They were standing around with their legs straight, their rear ends sticking up, and boy, were they hard to get over!" Another ordeal

of Black Tuesday was the qualifying swim. For that test, the students had to swim the length of an Olympic size pool underwater, taking only three

breaths. On top of this, they had to swim about a quarter mile. Five men dropped out at this point.

|

Kati stayed on. "Bob Diecks had prepared me for the absolute worst. He told me what they would do to me and prepared my attitude for that." In

retrospect, Kati estimates that to get through the school, attitude accounts for 75% and physical stamina only 25%.

Much of the first two weeks was spent in classrooms becoming oriented to diving equipment, diving physics, and decompression tables. But even during

this time Kati and the guys had to run and perform other physical feats.

They did one to two mile runs, pushups, calisthenics, and no less than 100 flutter kicks-where they lay on their backs, put their hands under their

rear ends, and kicked their legs, pulling them up and down while keeping them straight. "Those got to me after a while," says Kati. |

One day they did a mud run. In this they ran down to a muddy field and the instructor stopped right in front of a puddle. "O.K.," he said, "We are

going to play follow-the-leader." One trainee did a big belly-flop and went in head first. They all had to do the same thing, somersaulting and

wallowing in the mud. They rolled in it until they were caked with goo.

In between times they jogged, and the pace was faster than Kati was used to. This was where she learned that the guys were pulling for her. "They would

help me out by putting their arms around me and breeze me along." By this time the men were describing her as a "bundle of nerve."

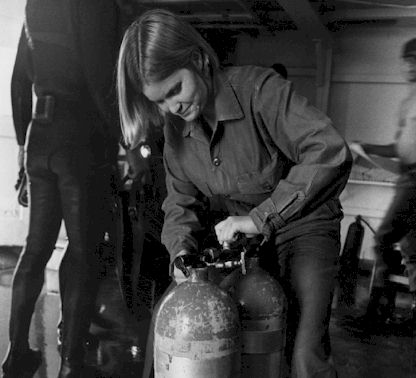

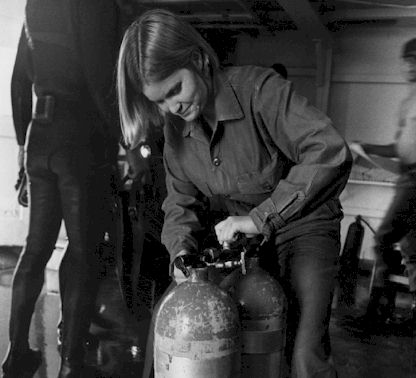

In the third week they began the pool sessions. This was the toughest part of the course. First they had to carry their tanks with one arm < tanks that

weighed about 90 pounds. "It took me two days to get that down," says Kati.

"We carried them from a truck to the swimming pool, which was up some steps. Then we would spend eight hours in the pool and have to repeat the process

the other way-four times. About this time I was really getting worn down. I thought, 'I'll never make it.' Plus, if we messed up we had to do pushups on top of everything else." At one point Kati was sitting on the pool deck in

her gear and her back began to buckle. Just as she began to sink backward, the instructor caught her eye. He laughed. She laughed. Then everybody laughed. "It picked up my morale a little. I was getting so tired, I think I

was in bed about 7 o'clock every night."

"But," she adds, "I knew I was going to finish it because I couldn't see myself dropping out."

During the pool harassment, the other girl dropped out. The men were surprised because, of the two, the other girl had been the most outspoken

during the classroom session in the first two weeks. Said one to Kati, "You know, we all thought she was going to finish, because she seemed to be more. . . whatever . . . and you were just sitting there." At this point, Kati

felt alone for the first time and began to wonder what she was doing it all for.

|

|

In the pool sessions their diving gear was ripped off, their air valves shut and, on top of that (and worse than that), they were harassed mentally to

wear them down, to make them feel awful. There was a rule that they couldn't be further than six feet from their buddies while in the water at any time.

If that happened, the buddy team who had committed the offense had to carry a 70-pound chain draped over their shoulders to keep them within six feet of

each other. They had to run with it and carry it wherever they went. Three teams were penalized in this way, but Kati managed to escape the exercise.

The instructors, however, decided that all of the students would have a race across the bottom of the pool, each person alone carrying the chain while

holding his breath. Kati made it about halfway across the length of the pool and had to come up for air. "I just couldn't go any more." Immediately

following that exercise, they had another relay race in the pool. The competing teams were called Cowgirls (Kati's team) and Cowboys (the others). "We won!" says Kati," and for our reward we had to hang from a fence by our

toes!" To do this, they put their hands on the ground so that their stomachs were facing the fence. Then they pushed themselves up, inching their toes over the top of the fence. "I saw all those toes up there and my arms went

limp," laughs Kati. "It was too funny. But the instructor said, 'We are not going to go until you get your toes up there,' so I finally got them up

there and just hung there."

When asked if she ever felt like crying during her ordeal, Kati is quick to affirm. "I got frustrated and started feeling kind of bad, and got some kind

of cold or flu toward the last part of it. I felt like I was going to die." But the crying didn't come until Kati messed up a written test. "One of my

buddies did, too. It was right after chow. We were sitting in this van and we were both crying." But Kati made up the test and got 100%.

The final week of the scuba school consisted of actual diving projects in San Diego Bay. The culmination was a 120-foot dive into the cold. Kati

suffered an ear squeeze, no doubt due to congestion brought about by her illness, but she didn't attach much importance to it. She had won her

diploma. |

|

Graduation

After graduating from Scuba school Kati was assigned to North Island, Coronado Air Station,

California, teaching survival at sea to air crewmen and pilots. She showed them what to

do if their airplane konks out at sea and they have to bail out. In the Pacific Ocean she demonstrated how to get out of parachute harnesses while

being dragged behind a boat at five knots. Sometimes the men are surprised that she is the teacher and safety swimmer. "You are going to save us?" one

student asked. "It's always asked good-naturedly," says Kati, who has found that most the men accepted her

as her classmates did throughout training. And for six months Kati was assigned to the Marine Mammal Training Department, Amphibious

Base, Coronado, CA.

|

Kati fully realized her fellowmen's attitude toward her on graduation day. One of them said to her, "You know, we never really accepted you as an equal

until you went through the mud run."

If you wonder why that is, Kati is quick to add, "Oh, I think it was because I got dirty with them." |

This article

was first published in Hillary Hausers book "women in sports - Scuba

diving" which came out in 1975. Many thanks to Kati Garner and Linda Beam

for their fantastic help with this article.

All material is © copyrighted by Kati Garner

We encourage other

women with professional or military diving experience to

contact us and tell the whole world

about it.